Hackathons on Rare Diseases

In recent months, we have been actively working with patient advocacy groups in the Rare Diseases communities. In particular, we have been getting together with civic hackers to better understand how information systems can be of benefit to the rare diseases communities, and using that knowledge to develop prototypes of software systems that could provide support for patients and their families.

Why Rare Diseases?

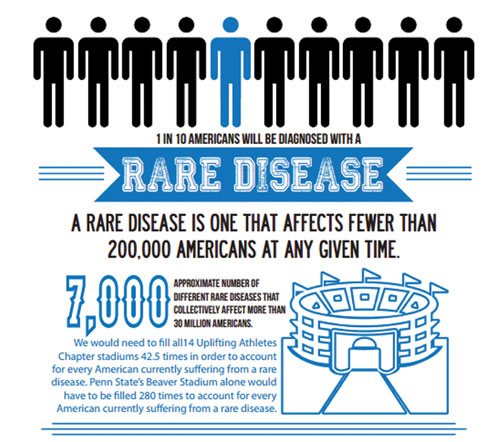

Rare diseases are defined as those that afflict populations of less than 200,000 patients, or about 1 in 1,500 people.

There are, however, about 7,000 rare diseases.

The patients affected by them, and their families, struggle due to lack of information and general knowledge on the nature and treatment of these afflictions.

It takes an average of 7.5 years for a patient to get a correct diagnosis for a rare disease, after having seen an average of eight doctors. By then, these patients have been treated for a variety of incorrect diagnoses and have missed the proper treatment for their case.

Most rare diseases are genetic and, thus, are present throughout a person's entire life, even if symptoms do not immediately appear. Many rare diseases emerge early in life, and about 30 percent of children with rare diseases will die before reaching their fifth birthday.

Although each one of the rare diseases by itself affects a relatively small number of patients, the combined 7,000 communities result in an impact of about 30 million people in the US and three million in the UK.

How They Cope

Due to the nature of rare diseases, it is difficult for healthcare professionals to become familiar with any of them and, much less, to develop expertise and competence with their treatment. Instead, families become the regular caregivers and, in turn, the qualified experts on the symptoms, manifestations, and day-to-day management of the patients.

Families also become very active in following the activities of the research community on topics that might be relevant to the particular disorders affecting their family members. In certain cases, these communities also drive research activities. Some even fund clinical trials for potential drugs. As a consequence, families in these communities are strong supporters of Open Access policies for publications that result from publicly funded research.

One of the common challenges for families in the rare diseases communities is to gather and consolidate the medical records of their patients, given that they will originate from a diverse set of medical institutions with a variety of medical records systems, as well as a large number of doctors from different specialties. It is also challenging for these families to network with others who might be afflicted by the same or similar disorders.

In this context, the rare diseases communities can greatly benefit from electronic health records (EHR) systems, which are designed to be managed by patient communities through a combination of Personal Health Records (PHR) systems and Health Information Exchanges (HIE). Given that this problem is common to most, if not all, of the rare diseases communities, it is also a natural target for pursuing a common effort that will benefit the aggregate of their 7,000 communities.

The economics of software development dictate that such systems can be developed at lower costs, in shorter time frames, and at higher qualities by taking advantage of Open Source methodologies.

The Hackathons

A series of four hackathons have taken place so far. The Hackathon events have been coordinated in collaboration with Ed Fennell, who is driving the Forum on Rare Diseases at the Albany Medical Center. Ed Fennell also recently gave a talk, raising awareness about rare diseases, at TEDxAlbany on November 14th.

During the hackathons, students and faculty from the State University of New York at Albany and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute joined forces with civic hackers and patient advocates to craft the outline of the type of information system that could track symptoms and phenotypes of any rare disorders.

Following agile methodologies, a first prototype has been crafted, which is hosted in Github at [https://github.com/EmilyAndHaley].

Currently, the development of the prototype has included an exploration of the many medical dictionaries that need to be combined in a typical medical information system, such as UMLS, SNOMED, RxNORM, CPT, and ICD. Each of these dictionaries is licensed under a variety of very specific terms. This leaves us with the impression that, in some cases, the licensing terms are longer than the medical dictionaries themselves.

The prototype has also led the group of civic hackers to discuss the technology that will be used for storing medical information that is gathered from a variety of sources. The sparse and highly interconnected nature of medical information has led the group to consider the use of Semantic Web technologies such as RDF and its associated serializations and querying mechanisms such as the SPARQL query language.

Synergies

The effort pursued in these hackathons have natural synergies with the work that many other organizations have done in the realms of:

• Personal Health Records

• Health Information Exchanges

• Quantified Self

• Data Sharing

• Education for medical students

• Testing for medical records systems

• Aggregation of medical information

• Interoperability of Electronic Health Records systems

• Open Source Electronic Health Records

The open source nature of the hackathon events makes it possible to take advantage of the network effects resulting from the resonance between the abilities and interests of many of these communities.

The hackathon activities will continue on a regular basis in 2014. If you would like to join and contribute to these efforts, please reach out and let us know.

Luis Ibáñez is a Technical Leader at Kitware, Inc. He is one of the main developers of the Insight Toolkit (ITK). Luis is a strong supporter of Open Access publishing and the verification of reproducibility in scientific publications.