System Architecture for Cloud-Based Medical Image Analysis

Introduction

In our previous blog post, we introduced VAMAS (Visualize, Analyze, Manage, medical images As a Service), our cloud-based Segmentation-as-a-Service application built with VolView, Resonant, and MONAI. That post focused on what VAMAS offers and why it matters. This follow-up takes a deeper technical dive into the system architecture decisions that enable such a platform.

Building a medical image analysis system is fundamentally different from typical ML inference services. The payload sizes are orders of magnitude larger, compliance requirements add architectural constraints, and the workflow expectations differ significantly from real-time APIs. This post explores these considerations and presents architectural patterns that address them.

From Prototype to Production

At Kitware, we distinguish between proof-of-concept systems and production deployments. VAMAS serves as a demonstration platform, showcasing what’s possible when you combine powerful open source tools like MONAI, VolView, and Resonant. It’s designed for exploration and evaluation with interested collaborators and customers.

When we work with commercial customers deploying into clinical or research environments, we follow a more rigorous architecture—one that demands higher reliability, stricter security controls, comprehensive audit trails, and the ability to scale with organizational growth. The patterns in this post reflect that rigor.

Think of VAMAS as the starting point. The architecture we describe here is what we build when that concept needs to serve real clinicians and researchers with real patient data.

Understanding the Requirements

Before designing any ML inference system, you need to understand the specific constraints of your domain. Medical imaging presents unique challenges that shape every architectural decision. A whole lung CT scan is not a single image. It’s a 3D volume consisting of 200-500 slices, each around 512×512 pixels, stored in DICOM format. Total size typically ranges from 100MB to 500MB per scan. MRI studies can be even larger, and whole slide pathology images can reach several gigabytes.

These data sizes have immediate implications. You cannot send a 300MB file through a typical API gateway in a synchronous HTTP request. Network transfer becomes a meaningful part of your latency budget. A 200MB upload over a 100Mbps connection takes 16 seconds before any processing begins. Unlike consumer-facing ML applications that require sub-100ms responses, medical imaging workflows tolerate longer processing times. A radiologist reviewing dozens of scans does not need instant results. Processing times of 1-5 minutes are acceptable, and for complex analyses, even longer waits are normal. This tolerance for latency opens up architectural options that wouldn’t work for real-time systems.

A busy hospital might process a few hundred scans per day. Even a cloud service supporting many institutions might see thousands of scans daily, which translates to only tens per minute. This is fundamentally different from consumer ML services handling thousands of requests per second. The challenge is not raw throughput but rather handling large data efficiently, maintaining reliability, and meeting compliance requirements.

Medical data falls under HIPAA in the United States and similar regulations globally. This means encryption at rest and in transit, comprehensive audit logs, access controls, and data retention policies. Some institutions require data to remain within specific geographic regions or even on-premise. These are not optional features but architectural requirements that must be designed in from the start.

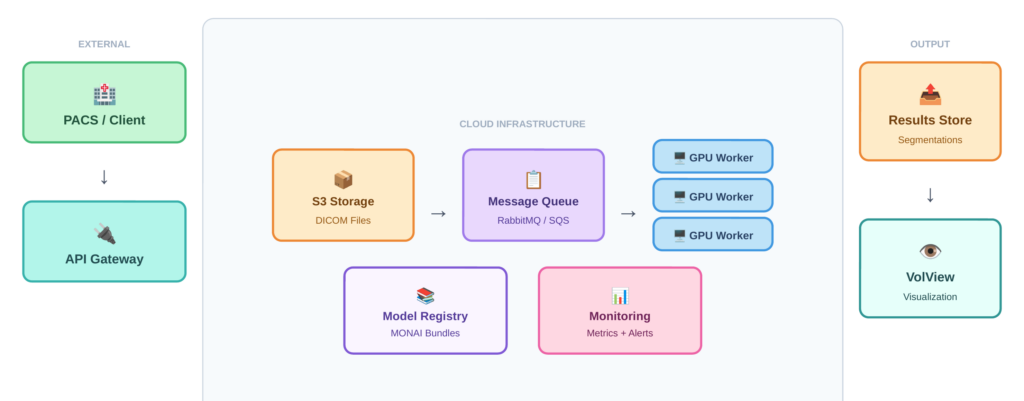

Architecture Overview

Given these requirements, medical image analysis systems benefit from an asynchronous, queue-based architecture rather than synchronous request-response patterns. This approach decouples data upload from processing, handles variable processing times gracefully, and allows the system to remain responsive under load. Figure 1 illustrates the overall system architecture, showing how these components connect: clients submit DICOM files through an API gateway, a message queue distributes work across GPU workers, and results flow back through cloud storage to a web-based viewer.

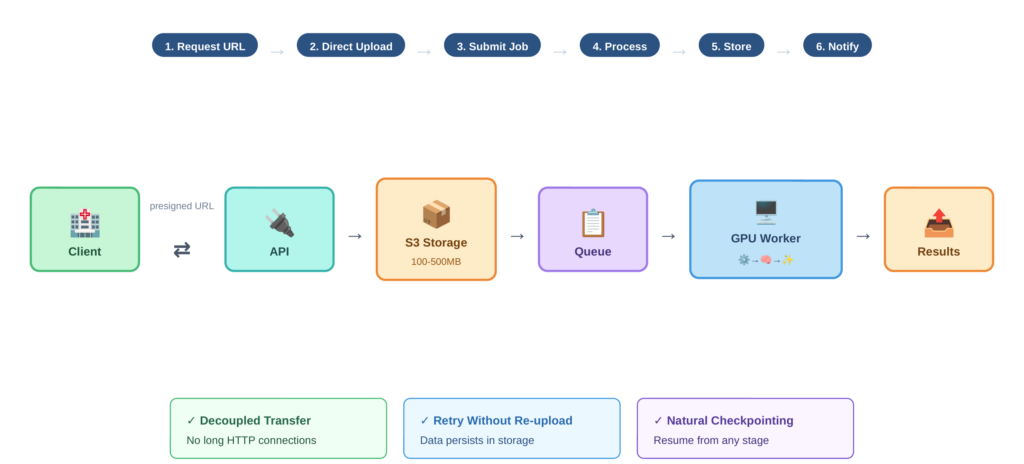

The Indirect Upload Pattern

Rather than uploading large DICOM files through your API gateway, the system uses indirect references. The workflow proceeds as follows:

- The client requests a presigned URL from the API

- The client uploads DICOM files directly to cloud storage (such as S3) using that URL

- Once upload completes, the client calls the inference API with the storage path

- The inference worker pulls data from storage, processes it, and writes results back

- The client retrieves results from storage or receives a notification

Figure 2 traces this data flow step by step, highlighting how the presigned URL mechanism keeps large imaging files off the API path and enables decoupled, resumable transfers. This pattern has several advantages. The client doesn’t hold a connection open for minutes during processing. You can retry inference without re-uploading data. Your inference fleet only needs fast internal network access to storage, not massive public ingress bandwidth. And you get natural checkpointing since data persists in storage.

Message Queue and Task Distribution

VAMAS uses RabbitMQ for message queuing and Celery for task distribution. When a user submits a segmentation request, it becomes a message in the queue. Worker processes consume these messages, perform the inference, and report results.

This architecture provides natural load balancing across workers, persistence of pending tasks if workers restart, visibility into queue depth for monitoring and scaling decisions, and isolation between tasks so one failure doesn’t affect others.

The choice of RabbitMQ over alternatives like Amazon SQS or Apache Kafka depends on your deployment context. RabbitMQ offers mature tooling and works well for moderate scale. SQS provides managed infrastructure if you’re already on AWS. Kafka makes sense if you need event streaming or extremely high throughput, though that’s rarely necessary for medical imaging workloads.

Worker Architecture

The worker fleet is where actual inference happens. Each worker runs on a GPU-equipped instance, pulls tasks from the queue, processes them, and reports results.

Model Server Considerations

In high-throughput synchronous systems, specialized model servers like NVIDIA Triton offer significant benefits through dynamic batching, GPU memory management, and multi-model serving. For asynchronous medical imaging workflows, however, these benefits are less pronounced.

Many teams running medical image analysis use PyTorch or TensorFlow directly in their workers rather than adding a model server layer. Preprocessing dominates the pipeline since DICOM parsing, windowing, normalization, and resampling often take longer than model inference itself. Throughput requirements are modest compared to consumer-facing APIs. Simpler deployment reduces operational complexity. And custom preprocessing pipelines integrate more naturally with direct framework usage.

That said, Triton or similar servers make sense when you run multiple models in a pipeline, when you want the optimization benefits of TensorRT, or when scaling to serve many institutions and throughput becomes important.

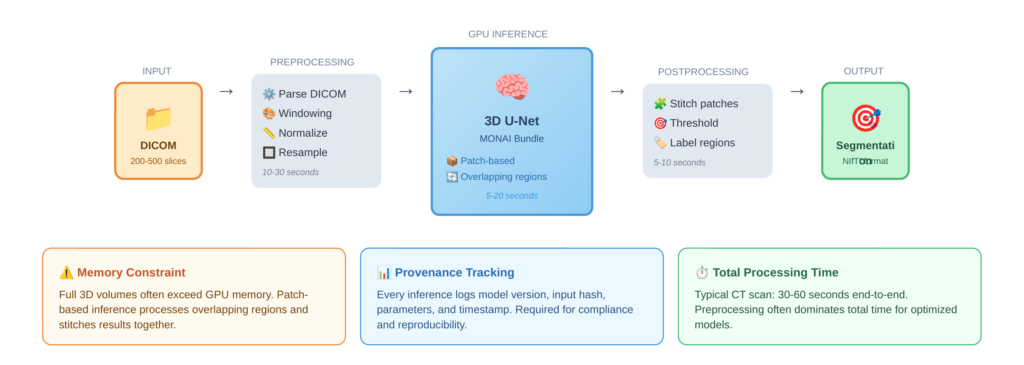

Preprocessing Pipeline

Medical image preprocessing is substantial. DICOM files must be parsed to extract pixel data and metadata. Windowing adjusts contrast for specific tissue types—lung, bone, and soft tissue each require different windows. Images are then normalized to consistent intensity ranges, and many models require resampling to specific voxel spacing. For 3D models, volumes may need to be processed in overlapping patches that are later stitched together.

This preprocessing can take 10-30 seconds per scan, often exceeding the model inference time. Optimizing this pipeline, perhaps through parallel slice processing or GPU-accelerated operations, can significantly improve overall throughput.

Figure 3 shows the complete worker processing pipeline, from raw DICOM input through preprocessing, patch-based GPU inference, and postprocessing to final segmentation output, along with typical timing for each stage.

GPU Memory Management

3D medical imaging models like 3D U-Net consume substantial GPU memory. A full-resolution CT volume may not fit in GPU memory alongside the model. The common solution is patch-based inference, where the volume is processed in overlapping regions and results are stitched together. This adds complexity but enables processing of arbitrarily large volumes on fixed GPU resources.

Model Management and Extensibility

A production system needs more than just the ability to run a single model. Users want access to multiple models for different tasks, the ability to bring their own models, and confidence that results can be reproduced. VAMAS leverages the MONAI bundle format for model packaging. A MONAI bundle contains the model weights, configuration files specifying preprocessing and postprocessing, metadata describing inputs and outputs, and optional training scripts. This standardized format makes adding a new model straightforward: users train a model, package it as a bundle, and upload it, where it appears as a selectable option.

For medical applications, knowing exactly which model version produced a result is not optional. Regulatory requirements, reproducibility, and debugging all demand comprehensive provenance tracking. Every inference session should log the model identifier and version, input data hash or reference, timestamp, all configuration parameters used, and output location and hash This enables questions like “which model version was used for patient X’s scan on date Y” to be answered definitively. It also supports rollback if a model update causes problems

Visualization Integration

Analysis results are only useful if users can visualize and interact with them. VAMAS integrates VolView for this purpose. VolView provides browser-based visualization of medical images without requiring local software installation. Users can view original DICOM data, overlay segmentation results on source images, adjust windowing and rendering parameters interactively, and compare results across different models or time points. This integration closes the loop from upload through processing to review, all within a single platform.

Scaling Considerations

While medical imaging doesn’t demand thousands of requests per second, the system must still handle variable load gracefully. The queue-based architecture provides natural scaling points. Queue depth is the primary scaling metric. When pending tasks exceed a threshold, add workers. When workers are idle, scale down. This is simpler than latency-based scaling for synchronous systems because the queue makes backlog visible. However, GPU instances take time to launch and initialize. The delay from scale trigger to ready worker might be 5-10 minutes. This favors maintaining some buffer capacity rather than aggressive just-in-time scaling, especially during business hours when demand is predictable.

Conclusion

Building a production medical image analysis system requires balancing many concerns: handling large payloads efficiently, meeting compliance requirements, maintaining reliability, enabling extensibility, and optimizing costs. The asynchronous, queue-based architecture described here addresses these concerns while remaining practical to implement and operate. These patterns reflect our experience deploying medical imaging solutions for commercial customers across healthcare, life sciences, and research.

Partner With Us

Whether you’re looking to deploy AI-powered medical image analysis, scale an existing prototype to production, or integrate advanced visualization into your clinical workflows, we can help. Our team has deep expertise in medical imaging, machine learning infrastructure, and the compliance requirements that govern healthcare technology.

We work with organizations at every stage, from early exploration to production deployment and ongoing support. If you’re building something in this space and want to accelerate your path to production, reach out to our team. We would love to learn about your challenges and explore how we can help. Contact us at kitware.com/contact or request a VAMAS demo to see these concepts in action.